Ticks are a common concern for dog owners across the UK, particularly during warmer months and after walks in woodland, grassland, or rural areas. If you’ve discovered a tick attached to your dog, you may find yourself asking whether it’s a deer tick or a dog tick and, more importantly, whether it poses a health risk.

The comparison between deer tick vs dog tick is often confusing, especially as the terminology is influenced by US sources and social media. In reality, UK dog owners encounter a smaller range of tick species, but the risks they carry still deserve careful attention. This guide explains the key differences, how to identify them, and what they mean for your dog’s health in a calm, practical, UK-relevant way.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Deer Tick vs Dog Tick: Identification and Behaviour in the UK

In everyday use, the terms deer tick and dog tick are often used loosely. In the UK, these names don’t always align neatly with the species definitions found in US-based articles, which is where much of the confusion originates. You might read warnings about the lone star tick online, for example, but thankfully, this species is not established in Britain.

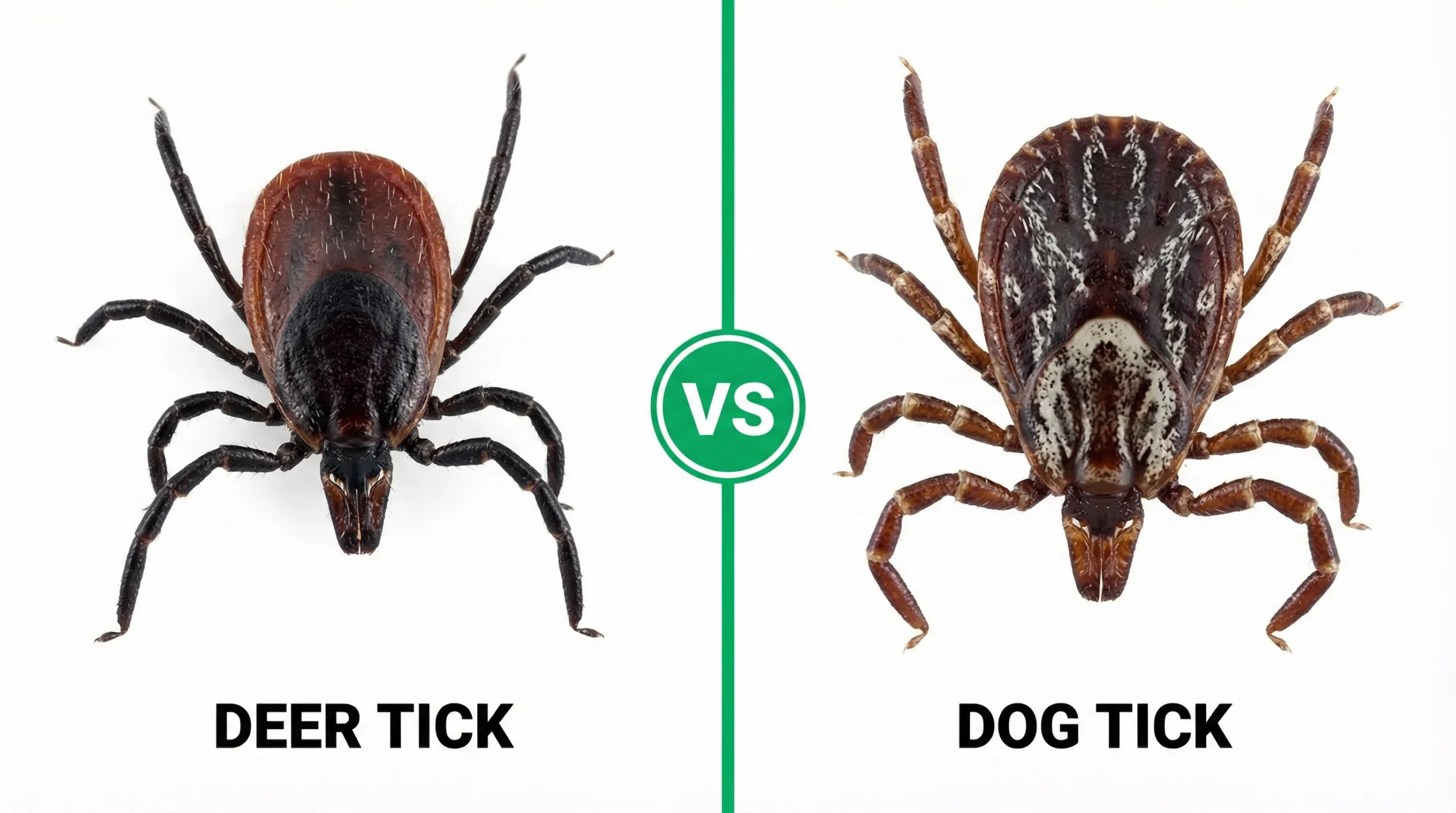

When UK owners refer to a deer tick (often called the blacklegged tick in online guides), they are usually describing a small, dark tick that is difficult to spot before it feeds. This generally corresponds to the tick species responsible for transmitting Lyme disease in the UK. The dog tick, by contrast, is typically larger, easier to see, and more noticeable once attached.

Both types attach to dogs in similar ways. They wait on vegetation and transfer onto passing animals, then attach firmly to the skin to feed. Ticks do not jump or fly, but they are highly effective at finding a host during walks through long grass, leaf litter, and woodland edges. Unlike fleas, which tend to move quickly through the coat, ticks attach firmly to the skin and remain in place for days, a key distinction also seen when comparing different external parasites such as cat fleas and dog fleas.

What matters most for owners is not the label, but recognising the physical differences and understanding the potential risks associated with each.

Physical Differences: Size, Colour, and Engorged Appearance

| Feature | Deer Tick (Sheep Tick) | Dog Tick (Meadow / Hedgehog Tick) |

|---|---|---|

| UK Common Name | Sheep Tick (Ixodes ricinus) | Meadow Tick / Hedgehog Tick |

| Unfed Size | Sesame seed (2–3mm) | Apple seed (4–5mm) |

| Key ID Feature | Dark body with black legs | Larger body, sometimes with lighter or patterned markings |

| Engorged Size | Small pea | Small grape or bean |

| Primary UK Risk | Most commonly associated with Lyme disease | Most commonly associated with Babesiosis (rare and regional) |

One of the most useful ways to distinguish a deer tick from a dog tick is by appearance, particularly size before and after feeding.

Deer ticks are small and flat before feeding, often no larger than a sesame seed. Their darker colouring allows them to blend easily into a dog’s coat, making them difficult to detect during routine checks. Because of their size, owners often don’t notice them until they have already fed for some time. Regular grooming routines, including bathing with suitable dog shampoos, can make ticks easier to detect early by keeping the coat clean and manageable

Dog ticks are generally larger and more robust, with a broader body and lighter or patterned markings. Even before feeding, they are easier to see against the skin or fur, especially on short-haired dogs.

After feeding, both types become engorged, swelling dramatically as they fill with blood. An engorged tick may resemble a small grey or beige grape or bean attached to the skin. This sudden size change is often what alarms owners, but it’s important to note that engorgement does not automatically mean disease transmission has occurred.

Because engorged ticks can resemble small lumps on the skin, some owners initially mistake them for growths, making it useful to understand how external parasites differ from conditions such as dog cysts or tumours.

Careful inspection of your dog after walks — particularly around the ears, neck, under the collar, armpits, groin, and between the toes — remains the most effective way to catch ticks early.

Found a Tick? How to Remove It Safely

If you have identified a tick on your dog, prompt removal is the best way to prevent disease transmission. You do not need a vet for this, but you do need the right technique.

Health Risks of Deer Ticks and Dog Ticks for UK Dogs

The primary concern with ticks is not the bite itself, but the potential for tick-borne diseases. In the UK, these risks are real but often misunderstood. Not every tick carries disease, and not every bite leads to illness. Tick exposure can vary by breed, age, and overall resilience, which is why understanding common canine health vulnerabilities can help owners spot when something is genuinely out of character for their dog

For dogs, health risks depend on factors such as:

- The tick species

- How long the tick was attached

- The dog’s overall health and immune response

Importantly, dogs may be exposed to tick-borne pathogens without showing immediate or obvious symptoms. This is why monitoring and prevention are more effective than panic-driven responses. Even after a tick is removed, the bite site may remain red or irritated. If your dog continues to scratch, using the best shampoo for dogs with itchy skin can help soothe the area and prevent infection.

Tick-Borne Diseases in the UK: What Dog Owners Should Know

Several tick-borne diseases are present in the UK, though their prevalence varies by region and environment. Understanding them helps owners make informed decisions without unnecessary alarm.

Lyme disease is the most well-known tick-borne illness in the UK. In dogs, it may cause symptoms such as stiffness, lameness that shifts between legs, lethargy, or reduced appetite. However, many dogs exposed to Lyme disease never develop clinical illness. Early tick removal significantly reduces the likelihood of transmission. For detailed maps and current risk areas, resources like Lyme Disease UK offer up-to-date monitoring.

Babesiosis is a rarer but emerging concern in parts of the UK. It affects red blood cells and may lead to weakness, pale gums, or dark urine in severe cases. Cases in the UK remain uncommon and are geographically limited, but awareness is important for owners who walk dogs in higher-risk areas.

Anaplasmosis is another tick-borne infection that can affect dogs. It may be associated with fever, lethargy, joint discomfort, or changes in blood counts. As with other tick-borne conditions, symptoms are not always immediate and may be mild or non-specific. Subtle signs such as head shaking, lethargy, or irritation can overlap with other common issues, which is why owners sometimes confuse tick-related discomfort with problems like ear mites or excess ear wax.

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is present at very low levels in the UK. While it receives attention due to human health implications, the risk to dogs is considered low. For most owners, awareness rather than concern is the appropriate response.

Across all these conditions, a consistent message applies: most tick bites do not result in disease, and prompt, careful removal remains one of the most effective protective measures.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a deer tick and a dog tick in the UK?

In the UK, the term “deer tick” usually refers to the Sheep Tick (Ixodes ricinus), which is small and dark. It is the primary carrier of Lyme disease. The “dog tick” often refers to the Hedgehog Tick or the larger Meadow Tick, which is easier to spot but less common. Both bite dogs and require immediate removal.

What does an engorged tick look like on a dog?

An engorged tick looks like a small, silvery-grey or coffee-coloured bean attached to your dog’s skin. It can grow from the size of a sesame seed to the size of a pea (up to 10mm). If you see a grey lump that wasn’t there yesterday, it is likely an engorged tick.

How do I remove a tick from my dog safely?

The safest method is to use a proper tick removal tool designed to extract the tick steadily without squeezing its body. These tools are designed to reduce the risk of infection during removal. Slide the tool under the tick, twist continuously until it detaches, and lift away. Never pull, squeeze, or crush the tick, as this can increase the risk of infection. If you are unsure about removing a tick yourself, major charities like the Blue Cross offer video guides, or you can visit your local vet. An example of a commonly used tick removal tool is the O’Tom Tick Twister.

Can I use Vaseline or alcohol to remove a tick?

No. Never use Vaseline, alcohol, nail varnish, or a match to remove a tick. These old methods can cause the tick to panic and regurgitate (vomit) infected stomach contents into your dog’s bloodstream, significantly increasing the risk of diseases like Lyme disease or Babesiosis.

What are the signs of Lyme disease in dogs?

Lyme disease symptoms may not appear for weeks after a bite. Watch for “shifting lameness” (limping that moves from leg to leg), lethargy, fever, and swollen lymph nodes. Unlike humans, dogs rarely get the “bullseye” rash. If your dog seems stiff or generally unwell after a tick bite, consult your vet.

Are ticks active in winter in the UK?

Yes. While ticks are most active in spring and autumn (March to October), they can remain active in winter if temperatures stay above 3.5°C. Wet, mild UK winters mean you should check your dog for ticks year-round, especially after walks in woodland or long grass.

What if the tick’s head gets stuck in my dog?

If the mouthparts break off during removal, don’t panic. It usually behaves like a splinter and will work its way out naturally. Clean the area with antiseptic and monitor for infection. Do not dig around with a needle, as this causes more irritation than the leftover tick part.